Things could be going better. You’re working hard to deliver on the competitive intelligence requests that come through your inbox, but as far as you can tell, very few people are consuming the insights and materials you produce.

To make matters worse, whenever someone does consume your output, there’s a decent chance you’ll find yourself on the receiving end of the dreaded message: “This is out of date.” Clearly, something has to change. If you keep doing CI in this ad-hoc fashion, you’ll permanently lose the trust of your colleagues—not to mention your sanity.

It’s time to create a business case. Don’t worry—we’re not going to give you a generic overview of what to include. Instead, we’re going to walk you through the three steps you need to take in order to put yourself in a position to create an ironclad business case:

- Get a sponsor

- Scope the program

- Consider (and rebut) alternative solutions

Here we go.

Step 1. Get a sponsor

Your sponsor is the senior-level member of your organization who’s willing to advocate for the creation of your CI program. To be an effective sponsor, this person needs to have a direct line of communication with your executive decision-maker (EDM).

(If you, personally, have a direct line of communication with your EDM, that’s fantastic—but for the purposes of this blog post, we’re going to assume that you do not.)

If you’re already doing CI on an ad-hoc basis, identifying your sponsor should be pretty straightforward. Who told you to start doing CI? If no one explicitly told you to start, why did you start? Who oversees the people you’ve been supporting?

Got someone in mind? Great! Go convince them to put their name at the top of your business case. To do this, you may need to create a miniature business case. Nothing crazy—just enough evidence of the need for a CI program to convince them to advocate for you.

Internal evidence

One way to show evidence of need is to survey the people you’ve been supporting with your ad-hoc efforts. This is probably your sellers. Ask them: How confident do you feel when you go up against the competition? How much value have you found in the competitive content I’ve created thus far? Do you think it would be impactful to have a dedicated, full-time CI expert?

If you want to take this one step further, you can use the data in your CRM to calculate competitive win rate—”Our sellers are losing competitive deals more often than they should be.”—and competitive frequency—”Our competitors are showing up in more and more deals over time.”

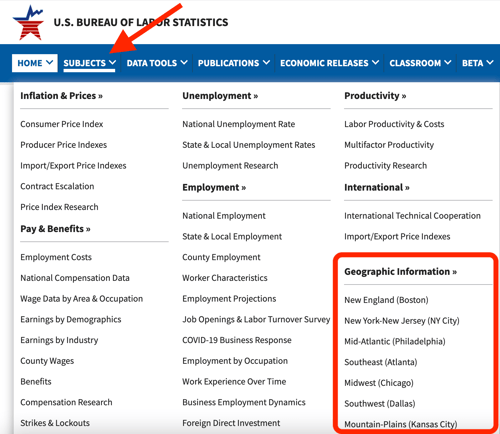

External evidence

Another way to show evidence of need is to find a third-party resource that speaks to the ongoing saturation of your market. Ideally, this would be a report published by an analyst firm (e.g., Gartner), but if such a report does not exist, you can always go to a review platform (e.g., G2) and use the data you find there to show that the number of companies in your space is rapidly growing.

With the right mix of internal and external evidence, you should be able to show your sponsor that it’s worth their time to work with you on your business case.

Step 2. Scope the program

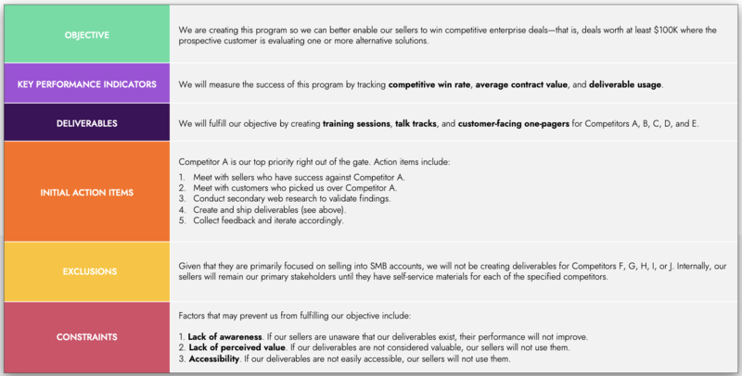

To scope your CI program is to determine its purpose, success criteria, deliverables, and constraints. By the time you’re done scoping, you should be able to answer questions like these:

- Why are we creating a CI program? What is the objective of the program?

- How will we determine whether the program is working?

- What are we going to do in order to fulfill our objective?

- What are we NOT going to do in order to remain focused on our objective?

- What factors might prevent us from fulfilling our objective?

You need to start with your objective; only when you’ve specified why you’re creating this program will you be able to figure out everything else.

Your sponsor is key here. Their proximity to your EDM is beneficial not only because it increases the likelihood of your business case being approved, but also because it ensures your alignment with the company’s overarching goals. Your sponsor knows what the executive team cares about, and they can help you identify a meaningful and measurable objective.

Ask your sponsor: “What are the company’s priorities, and how are you contributing to them?”

Listen closely to their answer and follow up with another open-ended question. Do that again, and again, and again until you’ve found a specific way to support your sponsor—and, by extension, the company as a whole. Let’s make this concrete with a simple example:

- Company priority: Grow the share of revenue coming from enterprise customers.

- Your sponsor’s contribution: Help sellers win enterprise deals.

- Your contribution: Help sellers beat enterprise-focused competitors.

From here, your next step is connecting with your initial stakeholders. (In our example, those would be your sales leaders.) We say initial because, eventually, you’ll be supporting all kinds of people across your company. That’s the beauty of specifying a meaningful and measurable objective at the very beginning: You’ll make a big impact right out of the gate, giving you the credibility, confidence, and momentum you need to grow your program.

In the meantime, when you connect with your initial stakeholders, the goal is to find out:

- How they define and measure success

- How they consume competitive intelligence

- Why the current method of consumption is suboptimal

- Which competitors—and kinds of intel—are most important

With this information, you’ll be able to define not only your objective, but also your KPIs, deliverables, and initial action items. Again, let’s make this concrete:

- Objective: Enable sellers to win competitive enterprise deals

- KPIs: Competitive win rate; average contract value

- Deliverables: Training, talk tracks, and one-pagers for [high-priority competitors]

- Initial action items: Meet with sellers who have success against [top competitor]; meet with customers who picked us over [top competitor]; conduct secondary web research to validate findings; create and ship deliverables; collect feedback

At this point, you’re almost done scoping your program—which raises a question: What do you do when someone submits a request that falls outside of your scope?

Well, first of all, you need to ask questions. Why does this person need the thing they’re asking for? If you can get to the root of the request, you and your colleague may realize that what they actually need already exists. This is a win-win: They get what they need, and you save time.

Alternatively, if the thing your colleague needs does not exist, the question then becomes: Does this warrant a change in scope? If the answer is no, keep in mind that:

- Your colleague deserves an explanation. This person wouldn’t be coming to you if they weren’t feeling some kind of pain. Lead with empathy, and rather than simply telling them that you don’t have time, tell them why you have to prioritize your other work.

- You can probably help them help themselves. You don’t have time to do a messaging teardown—but you almost certainly have time to share best practices and resources. Helping your colleagues help themselves is a good way to build affinity for your program while staying focused and avoiding burnout.

If you get a request that does warrant a change in scope, make sure to notify your sponsor and your stakeholders, as you’ll need to adjust your timelines. In these situations, our notes on leading with empathy and helping others help themselves are still very much applicable.

One final thing to consider before creating your scope statement: constraints. What factors might prevent you from fulfilling your objective? Answers will vary from one program to the next, but in general, adoption is the X factor: If your insights and assets are difficult to access or lacking in value, or if no one is looking for them in the first place, then you’re not going to fulfill your objective.

The good news is that, because you’re doing all this up-front discovery work with your sponsor and your stakeholders, it’s unlikely that your insights and assets will be lacking in value. Accessibility is a technological concern—learn more about Crayon’s suite of software integrations here—and lack of demand is … well, it’s simultaneously a technological concern and a cultural concern. You can learn more about the role culture plays in competitive intelligence here:

The tangible output of all this scoping work is your scope statement. Here’s an example of what that might look like:

Step 3. Consider (and rebut) alternative solutions

With your sponsor secured and your scope stated, you’re almost ready to write your business case. There’s just one more question to consider: What are the alternatives to creating a CI program, and why are those alternatives inferior?

Well, the most obvious alternative is to keep doing CI on an ad-hoc basis, and the list of reasons why this is an inferior option is a long one. This is a good time to remind you that the person to whom you’re delivering this business case is exceptionally busy, which means you need to be concise. If your retort to this objection is too long, it won’t make much of an impact.

So, ask yourself: Given who your EDM is, what has the best chance of resonating? If your EDM is the CMO or the CRO, the risk of lost revenue probably has the best chance of resonating. Here’s an example of what you might say: “When CI is done on an ad-hoc basis, deliverables rapidly fall out of date, leading to loss of trust and low usage rates. Sellers end up navigating competitive opportunities without any support, leading to lower win rates and slowed revenue growth.”

If your EDM is the Chief Product Officer or the Chief Strategy Officer, the risk of getting blind-sided and “playing from behind” probably has a better chance of resonating. Here’s an example of what you might say: “When CI is done on an ad-hoc basis, we’re unable to predict what the competition will do in the future. We’re stuck in a reactive position, making adjustments to our plans on the fly rather than proactively baking in our predictions at the earliest stages of planning.”

Two other alternatives that you should be prepared to rebut are:

- Not doing CI at all, and

- Allowing everyone to do a little bit of CI on their own.

Although these are technically unique objections, you should be able to lean on the same core sentiments that we’ve already discussed. If your EDM is the CMO or CRO, lean on the risk of lost revenue; if your EDM is the CPO or CSO, lean on the risk of getting blind-sided.

Present the best business case your EDM has ever seen

Creating a business case isn’t a particularly fun activity. But if you want to do CI the right way, you have to convince at least one person in the C-suite that capturing, analyzing, and activating intel is a full-time job.

That’s intimidating—but it’s certainly not impossible. At the end of the day, all you really need to do is talk to the right people until you’ve identified a specific problem that can only be solved with CI. As long as you’re prepared to explain why that problem is a real problem and why it can only be solved through the creation of a formal CI program, you’ll be off and running in no time.

Related Blog Posts

Popular Posts

-

The 8 Free Market Research Tools and Resources You Need to Know

The 8 Free Market Research Tools and Resources You Need to Know

-

How to Create a Competitive Matrix (Step-by-Step Guide With Examples + Free Templates)

How to Create a Competitive Matrix (Step-by-Step Guide With Examples + Free Templates)

-

6 Competitive Advantage Examples From the Real World

6 Competitive Advantage Examples From the Real World

-

24 Questions to Consider for Your Next SWOT Analysis

24 Questions to Consider for Your Next SWOT Analysis

-

How to Measure Product Launch Success: 12 KPIs You Should Be Tracking

How to Measure Product Launch Success: 12 KPIs You Should Be Tracking